Every spring, summer, and early fall, parents of rising high school seniors across America take part in a uniquely American tradition: hiring a professional photographer to take their child’s senior portraits.

Ask anyone outside the U.S. what comes to mind when they hear “senior portrait,” and they’ll likely think you’re talking about a grandparent — something that, honestly, should become a tradition too!

I didn’t grow up in the U.S., and the first time I heard about this kind of photography was when a client asked me to photograph a senior portrait. My American wife and oldest son had to explain what this photograph means, why it matters and how it is not only an important way of marking a particular milestone, but a way of telling a graduate’s story.

My son Max and his senior portraits.

After that first confusing request, I’ve photographed many senior portraits and I’ve come to understand what my clients are really looking for: a way to mark a turning point, to tell a personal story, and to preserve it. In order to do this well, I felt that I had to explore the roots of this very American ritual. Now that I have a place to write about it, I want to share what I’ve learned – including some senior portrait ideas.

I hope it’s as fun for you to read as it’s been for me to write and research.

Photography as a Luxury (1840s–1890s)

Whenever I think about the business of photography, especially portrait photography, I recognize that my entire business was made possible by three major historical shifts: the growing affordability of portraiture, making it a powerful social equalizer; the rise of accessible photographic technology; and the commercialization of emotion. Without these three historical tidal waves, we’d still be living in a world where portraits were a luxury item for the wealthy and I would be out of a job.

Before commercialization of photography, made possible by a revolutionary process called the daguerreotype, portraits were painted by an artist. Visit any museum and walk through the portrait galleries: wall after wall of oil paintings, all commissioned by wealthy patrons and painted by artists over weeks, months, or even years. The most famous of the commissioned paintings is, of course, the Mona Lisa.

Daguerreotypes changed all that. They weren’t cheap, and they still required the expertise of a professional photographer, a studio, and specialized equipment. But they were far more accessible than painted portraits. By the mid-1800s, daguerreotype studios were springing up across cities and towns, catering to middle-class families who wanted to mark life’s milestones – much like we do now with senior pictures.

Photos from very early 1900s from my family archive.

One of my ancestors was a Russian serf. When serfdom was abolished in 1961, his former master hired a photographer to create a daguerreotype to mark the occasion. The photograph was formal and deliberate — a visual record of what was likely the most important moment in his life. Though I haven’t been able to find that specific image, I’ve been lucky enough to discover four daguerreotypes of my ancestors from the early 1900s in Russia, complete with studio stamps on the back.

The daguerreotypes, a part of my family’s story, were carefully preserved by my grandmother and passed to me. This is our family’s story that I told my kids. And I hope they’ll share it with my grandchildren.

These portraits, made possible by early photographic studios, connected my middle-class family to a visual legacy that once belonged only to the elite.

The Birth of Yearbooks (1900–1920s)

As high school education became more widespread in early 20th-century America, yearbooks emerged as an essential way to celebrate graduates — many of whom were the first in their families to earn a diploma.

Yearbooks didn’t just record student names; they told stories — of individuals, of schools, and of communities. In small towns and rural areas especially, yearbooks became part of local history. The yearbook captured names, faces, and everyday moments that might otherwise have faded with time. A yearbook was also a powerful message to students:

You were here. Your time mattered. You belong to this place, and you contributed.

The town of Everett, MA, just north of Boston, has digitized copies of yearbooks going back to 1916.

Technological advances once again played a key role. The daguerreotype was long gone, and in its place came the Kodak Brownie camera introduced in 1900. This small, simple to use and affordable camera, sold for $1 (about $35 in today’s money), once again, moving photography from luxury into a part of daily life. If you want to read more about the Brownie camera, here is a link to a great blog post on the subject, with an image of the Brownie camera.

Combined with improvements in typesetting and mass printing, this allowed schools to produce affordable, photo-rich yearbooks at scale.

Photographers and printers recognized the opportunity. Instead of waiting for students to visit their studios, they began setting up in schools to ensure consistency, affordability, and — let’s be honest — volume. For many students, their yearbook portrait was their first official photograph.

Post-War Prosperity and Suburban Culture (1950s–1970s)

The end of World War II brought prosperity and a sense of optimism to the rapidly growing American middle class. The optimism was intricately tied to a lifestyle change. Wartime rationing and frugality admired in the pre-war era were replaced by lavish consumerism. New TVs, larger appliances, and cars, barbecues, and the perfect green lawn —all of it needed to be celebrated, documented, displayed, and preserved.

Here again, photography played a crucial role in capturing family milestones, such as first cars, new homes, and, of course, school graduations. It was a visual archive of middle-class family achievement.

The most famous business case of commercializing the post-war emotional optimist was the Hallmark card.

Hallmark cards allowed Americans to celebrate every day, as well as holidays, birthdays, and other milestone events, marking them with a card, something to put in a scrapbook. No scrapbooks would have been complete without a photograph!

What could be more important than a photo marking the end of childhood, the transition into adulthood?

My friend Caryl’s mom and dad 1940s.

The Explosion of Individual Style (1980s–1990s)

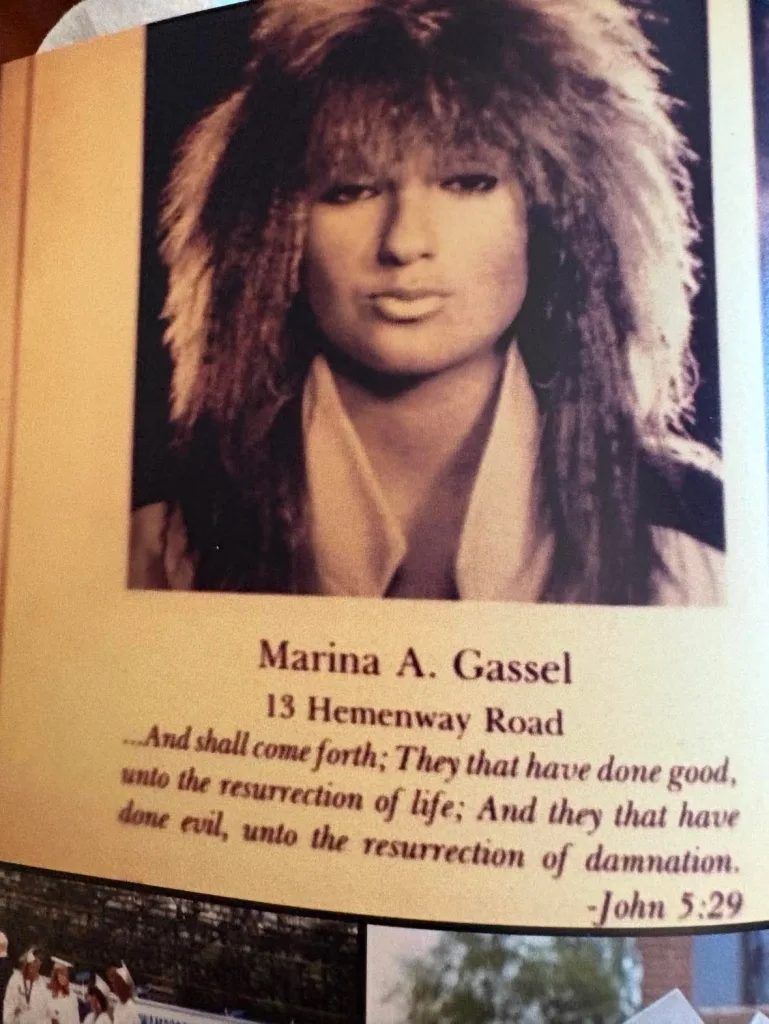

By the 1980s and 90s, traditional headshots were out, and full-blown senior portrait sessions were in. Props, outfit changes, outdoor settings, and soft-focus glamour shots became the norm. It wasn’t just a photo anymore — it was a production.

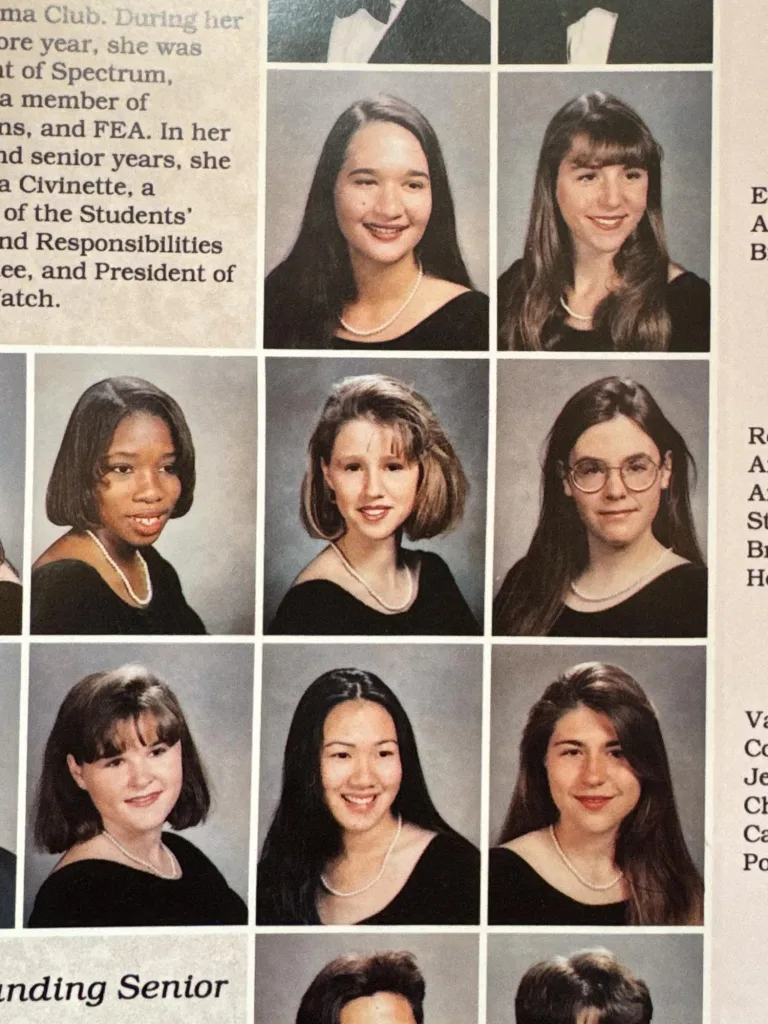

Fragment of my friend Stephanie’s yearbook and her senior photo, 1995.

Long before anyone heard of Instagram, high school seniors were already using photography to express who they were. Portrait packages came with wallet-size prints to trade with friends, and oversized framed prints for the mantle at home.

Once again, convenience and commercialization made it all possible. Mall-based studios like Olan Mills and Lifetouch offered photo session packages that were accessible, affordable, and customizable. You could walk into a Sears and walk out with a portfolio of graduation photos — one more symbol of how photography had become embedded in American life.

I’m not a historian — I’m a photographer. But from what I’ve seen and heard, these portraits were more than a trend. They were a way for teenagers and families to hold onto identity, legacy, and pride — one carefully posed image at a time.

A yearbook photo of a family friend.

The Social Media Era (2000s–Present)

What began as expressive senior portraits in the 1990s laid the groundwork for today’s image-driven teenage culture, marked by the arrival of the smartphone. Today’s phones have cameras that would have been the envy of any professional photographer from a decade ago, complete with editing software.

Today, a senior portrait is not just a way to mark the graduation milestone; it is a part of personal branding, an attempt to move away from the selfie to professional senior photos experience that documents the passage into adulthood, which is part of telling a teenager’s personal story.

The Story That Still Needs to Be Told

In the end, the senior portrait is more than a quirky American tradition, it’s a kind of equalizer, a photo of every graduate, regardless of background, income, or future plans. It’s a way for a teenager to say: I matter. This moment matters. Remember it.

And maybe — just maybe — today’s creative senior portrait photos will be something a teenager can proudly show their own kids someday.

At least, that’s my goal.